Wound Care & Management

The guiding principles of wound care have always been focused around defining the wound, identifying any associated factors that may influence the healing process, then selecting the appropriate wound dressing or treatment device to meet the aim and aid the healing process.

A structured approach is essential, as the most common error in wound care management is rushing in to select the latest and greatest new wound dressings without actually giving thought to wound aetiology, tissue type and immediate aim.

If best patient outcomes are to be achieved, applying evidence-based wound management knowledge and skills is essential.

This wound and dressings guide will identify some of the most common wound types and guide you in setting your aim of care and selecting the best dressing or product to achieve that aim.

Wound Care Assessment

Holistic Assessment (HEIDIE)

The first thing to do before addressing any wound is to perform an overall assessment of the patient. An acronym used to guide this process step by step is HEIDIE:

- History - The patient's medical, surgical, pharmacological and social history.

- Examination - Of the patient as a whole, then focus on the wound.

- Investigations - What blood tests, x-rays, scans do you require to help make your...

- Diagnosis - Aetiology / pathology.

- Implementation - Implementation of the plan of care.

- Evaluation - Monitor, assess progress and adjust management regimen, refer on or seek advice.

So, with this in mind, and having completed a thorough overall assessment, a wound assessment can now be conducted.

The five parameters to consider in wound assessment include:

1. Tissue type

Necrotic, infective, granulation, hypergranulation, poor-quality granulation, epithelium and macerated.

2. Wound Exudate

(Type, volume and consistency)

3. Periwound Condition

(This is the area that extends 4 cm from the edge of the wound, although we are now being asked to consider the skin up to 20 cm from the wound edge where possible)

4. Pain level

(At dressing changes, intermittently or consistently)

5. Size

(length, width and depth)

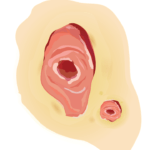

Wound Tissue Types

Descriptors used to identify the tissue found in wounds are:

- Necrotic eschar

- Necrotic slough

- Infective

- Granulation

- Hypergranulation

- Poor-quality granulation

- Epithelium

- Macerated

Necrotic Tissue

Ideally, the quickest (and often safest) way to remove necrotic tissue is to involve a surgeon who will then surgically debride the offending tissue.

If this is not possible, then a skilled clinician may be able to conservatively sharp-debride the tissue to just above the viable base.

If this is not possible, then dressings known to aid autolytic debridement should be selected and used according to manufacturer's instructions. An important aspect to consider is that when debriding wounds autolytically the wound may appear deeper as the necrotic debris is removed, revealing the true depth of the wound.

Important: Without a doubt, removal of necrotic tissue and management of infective tissue are two priorities in wound care.

Granulation Tissue

Granulation tissue (firm, beefy red tissue) requires some exudate management and protection.

A dressing that maintains a minimally moist environment and protects the tissue, is generally required.

Hypergranulation

his soft, gelatinous, highly exuding tissue requires specific treatment. Some clinicians believe the use of silver nitrate (burning the tissue back) is the best option.

It has been my experience that an approach to bacterial load, direct pressure and dressings that will manage moisture are more acceptable. Newer research is also indicating that hypergranulation is more than likely associated with biofilm and hence, microbial load (Swanson et al. 2022).

Infective Tissue

Infective tissue is best removed when possible by employing the same methods as with necrotic tissue. Antibiotics need to be prescribed when the wound is causing spreading and systemic infection. Exercise caution when debriding infected necrotic tissue as bleeding may occur; generally a few days of antibiotic therapy prior to debriding is ideal when performing in a community setting.

If the wound is locally infected, the clinician may choose to manage the infective tissue with debridement and topical antimicrobials (not topical antibiotics) (Lipsky & Hoey 2009). Topical antibiotics may be used in specific circumstances - for more information, refer to Wound Infection in Clinical Practice: Principles of Best Practice .

Another consideration if colonisation is of concern, is to use generalised body skin-antiseptic cleansers to reduce the possibility of bacteria colonising from one area to another.

Epithelium

The pale, pink/mauve tissue usually found at the edges of wounds, healing by secondary intention, requires protection. If the wound is superficial/partial thickness then islands of epithelium may also be found sprouting up from skin appendages.

This tissue responds poorly to too much moisture and in most cases a dressing that protects this tissue from the effects of moisture is used. The use of barrier agents ensures this. The area is also particularly susceptible to friction and shear, which must be eliminated.

Poor Quality Granulation (Agranular)

The term used to describe pale, grey/brown/red granulation tissue.

The general approach is to use an antimicrobial and exudate-management dressing, reviewing blood profiles and concentrating on nutrition to help grow stronger better-quality tissue.

Maceration

The term used to describe pale, grey/white tissue found at the edges of a wound. Some clinicians believe maceration is overhydrated keratin and not to be worried about, however, take note that when appearing on weight-bearing areas of the body the soft, soggy edges of a wound will collapse under pressure and will become larger.

With the above information, it is now time to undertake wound care specific to the type of wound.

Wound Tissue Types

Dressing Surgical Wounds

Most surgery can be categorised into two groups: elective ('clean') and emergency (this is often referred to as 'dirty').

A surgical wound of the latter category has a higher incidence of dehiscence or complications.

Dehiscence is defined as:

'Separation of the layers of a surgical wound, it may be partial or only superficial, or complete with separation of all layers and total disruption.'

(Miller-Keane Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health 2003)

There are a number of well-identified risk factors that can lead to wound dehiscence, including being overweight, increasing/advanced age, poor nutrition, diabetes, smoking and having had radiation therapy previously in the area.

The elective case has the opportunity to correct some of these risk factors; however, the emergency case may not have such an opportunity.

Suture Line

The simple, straightforward suture line is generally treated with a dressing that will manage a small amount of anticipated, early inflammatory exudate and provide a waterproof covering.

All surgical wounds do require support and this is an important factor both for reducing oedema and ensuring patient comfort.

This type of dressing is generally left intact for five to seven days and then removed for inspection of the suture line, with the view to remove the staples or sutures as prescribed.

Suggested dressings to achieve the aims for simple suture lines include: Opsite™ Post-Op and Mepore Pro™.

Composite dressing.

Features: Absorbent, self-adhesive, cushioned, breathable, waterproof.

Uses: Surgical wounds, cuts, abrasions, low to moderately exuding wounds.

Examples: Opsite™ Post-Op, Mepore Pro™.

Care of this simple suture line then involves continued support and hydration. For this, some surgeons prefer supportive adhesive flexible tape for ongoing scar hydration, such as Fixomull™ and Mefix™.

Adhesive flexible tape.

Features: cut to size, adhesive, flexible, allows hydration.

Uses: fixing primary dressings, catheters and tubes.

Examples: Fixomull™, Mefix™.